Welcome to my nostalgia project, where I delve into a computer vision task that blends childhood memories with cutting-edge technology. In this post, I’ll walk you through the creation of a machine learning model designed to tackle a unique challenge: finding Waldo and his four friends (Wenda, Wizard, Odlaw, and Woof) in the iconic “Where’s Waldo?” series using YOLO. This project not only highlights the power of advanced object detection but also celebrates the playful challenge of spotting hidden characters in a sea of visual complexity.

The primary goal of this project was to create a practical tool that leverages machine learning to simplify the classic “Where’s Waldo?” experience. By training a YOLO model, I aimed to enable users to take a photo of a book page with their cell phone and have it automatically identify Waldo and his four friends in real time. This functionality not only enhances the interactive enjoyment of the “Where’s Waldo?” series but also demonstrates how advanced object detection can be applied to everyday tasks. The vision was to make character identification effortless and immediate, turning a challenging visual puzzle into a seamlessly integrated digital experience.

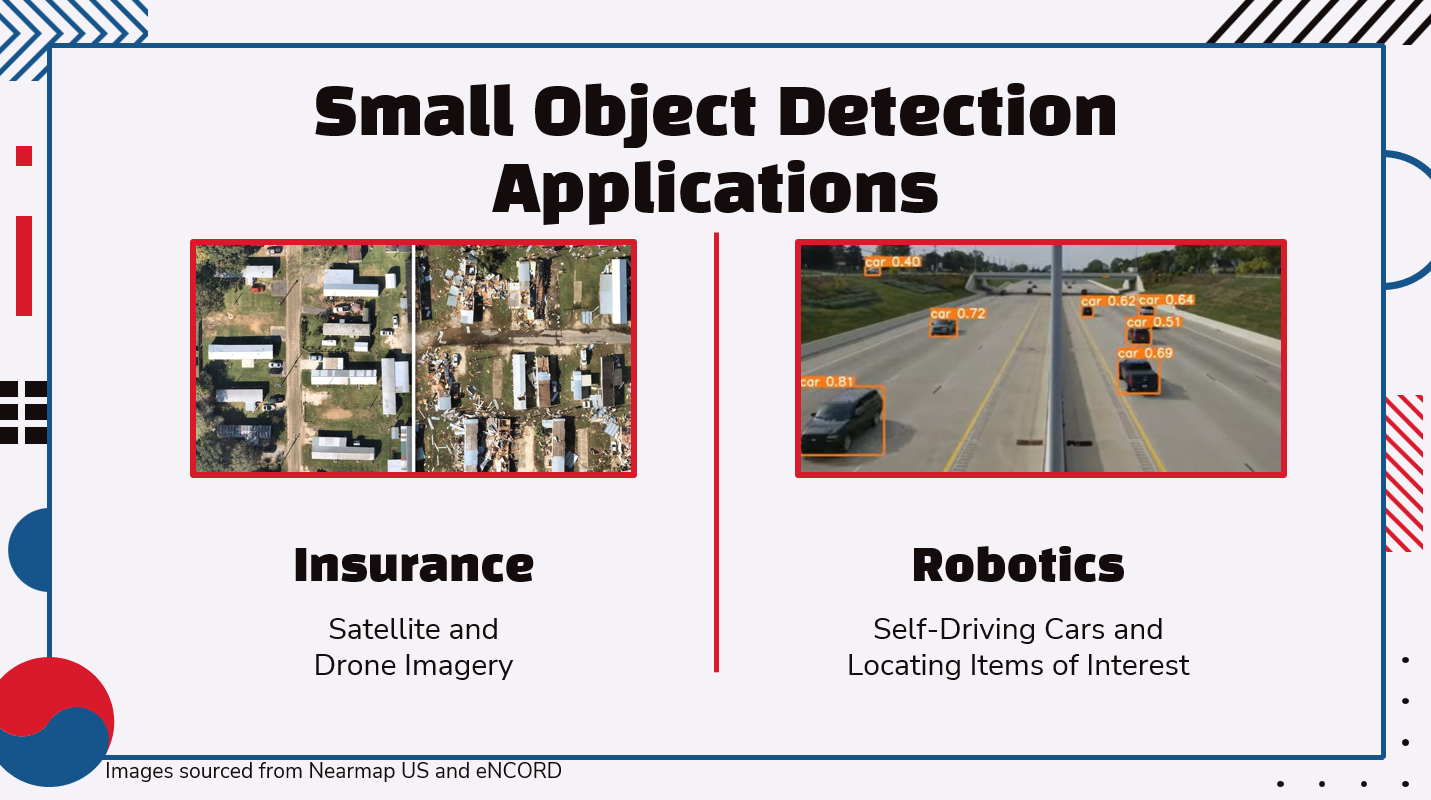

This project extends beyond the playful realm of “Where’s Waldo?” to address critical challenges in the field of small object detection, which is crucial for technologies like self-driving cars and drones. Detecting small or partially obscured objects in real-time is a common hurdle in these applications, where precision and speed are paramount. The techniques refined during this project, such as focusing on less obstructed features and managing varying image conditions, are directly applicable to these domains. For self-driving cars, this means improved detection of pedestrians, cyclists, and other small hazards. For drones, it enhances the ability to identify and track small objects or obstacles in dynamic environments. By addressing the complexities of small object detection in a controlled setting, this project provides valuable insights and methodologies that can be adapted to improve the robustness and accuracy of object detection systems in more complex, real world scenarios.

Table of Contents

Data Gathering

Data gathering for this project presented unique challenges due to the need to account for the imperfect conditions of real-world photographs taken with a cell phone. Many of the existing datasets I found online featured ideal conditions of perfect lighting, flat pages, and high resolution. Unfortunately, these conditions don’t accurately reflect the varied environment users encounter with a typical cell phone camera. To address this, I created my own dataset using an iPhone, capturing photos of full puzzle pages (2 pages). Initially, this approach proved problematic because the model struggled with the low resolution of these images, particularly given the small size of Waldo. To improve performance, I refined my data collection strategy by focusing on single page photos, which I then programmatically divided into 640 by 640 pixel tiles with slight overlaps. This adjustment allowed the model to better handle the resolution and intricacies of the task, leading to more accurate and effective character detection.

Modeling and Evaluation

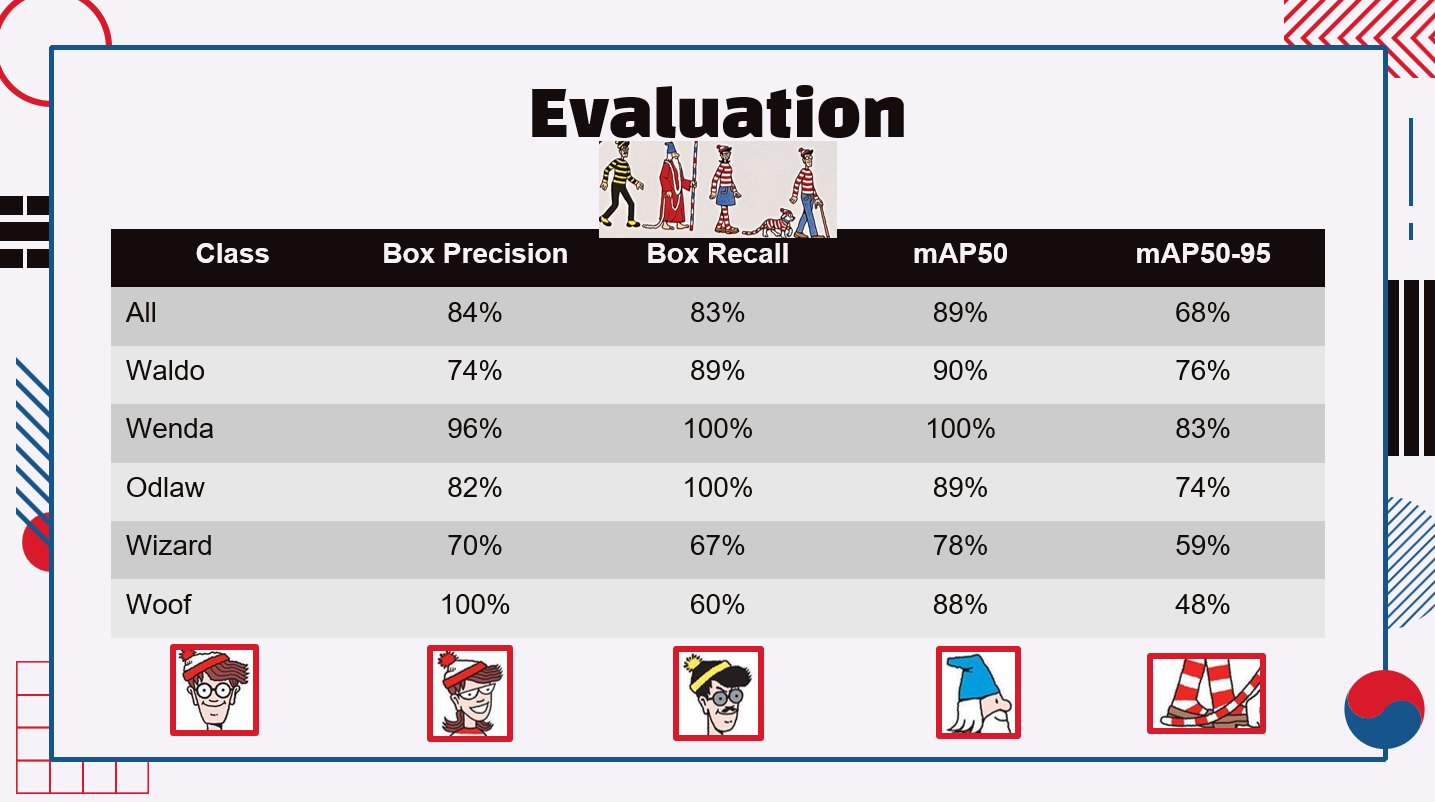

For the modeling phase of this project, I utilized YOLO, Python, and the Ultralytics library to tackle the challenge of detecting all five characters simultaneously. I experimented with two distinct approaches to determine the most effective strategy for character identification. The first approach focused on detecting only the heads of the characters, under the assumption that the heads would be less obstructed in the photos despite being smaller in size. The second approach aimed to detect the full characters, which provided a larger target but was often hindered by obstructions. By comparing these methods, I evaluated whether the advantage of larger pixel size outweighed the difficulties posed by obstructions. Ultimately, the head only model proved to be more successful, yielding superior results and more accurate detections. This approach balanced the trade-off between size and visibility, demonstrating that focusing on smaller, less obstructed features leads to better overall performance.

Model Misses

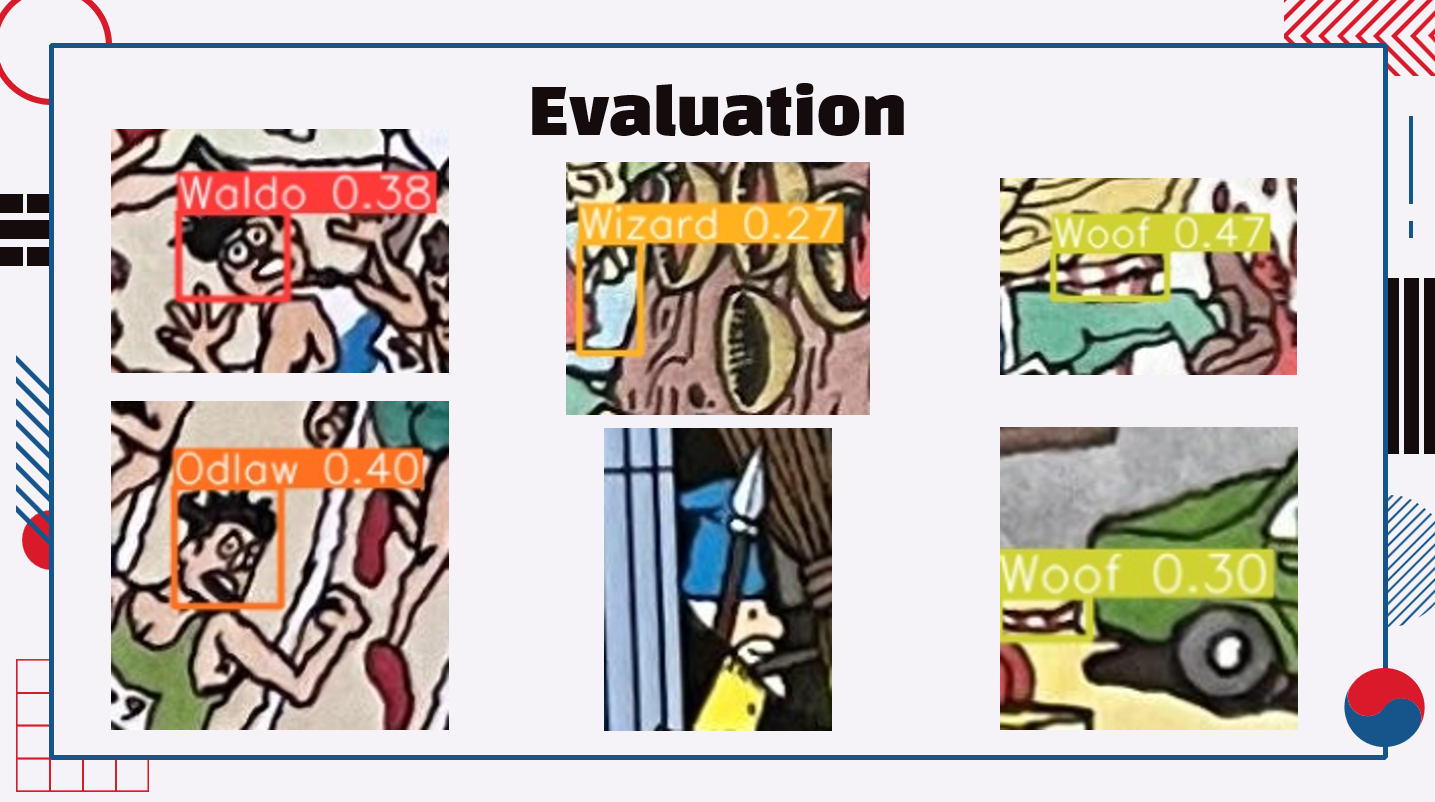

Model misses were an inevitable part of this project, highlighting the challenges inherent in object detection.

For example, in the two photos on the left, the characters have hairstyles and large eyes that resemble Waldo and Odlaw, leading the model to incorrectly identify them based on these features. Additionally, the lower character’s teeth were mistaken for Odlaw’s mustache.

The top middle photo features an object with a shape and color similar to the wizard’s hat, which confused the model. The bottom middle photo is the wizard himself, whose recognition was hampered by heavy obstruction from surrounding elements.

The lower right photo (Woof’s tail) presented difficulties due to his small size and low pixel count, making accurate detection challenging. The upper right photo is actually a shirt sleeve that resembles Woof’s tail, further complicating the model’s ability to distinguish between the character and non-character elements.

These misses underscore the need for continued refinement in object detection models to handle diverse and obstructed visual information effectively.

Learnings

This project provided valuable insights into the performance of YOLO for detecting characters in the “Where’s Waldo?” series, revealing important nuances in object detection. Different characters exhibited varying levels of precision and recall, influenced largely by their shapes and the nature of their surroundings. For instance, Woof’s tail was often unobstructed, which contributed to high precision, but Woof’s small size led to lower recall rates as the model struggled with detecting such small features.

The project also demonstrated the capabilities and limitations of small object detection. The model effectively identified objects as small as 20x20 pixels, but background noise, imperfect photo conditions, and object obfuscation meant that achieving reliable results generally required objects to be around 50x50 pixels. This highlights the trade offs involved in balancing object size and detection accuracy.

Tiling images emerged as a crucial technique for this project, allowing for detailed analysis without rescaling images. However, tiling could lead to loss of critical information. Although overlapping tiles by 40 pixels helped mitigate information loss, challenges persisted, such as cutting off faces at the edges of tiles. These experiences underscore the importance of finetuning both data preprocessing methods and model parameters to enhance detection performance in practical applications.