This post is a behind the scenes look at how different parts of our autonomous submarine went from works on paper to works in the pool. It covers the unglamorous parts: debugging, rebuilding, and iterating. It also covers the breakthroughs that actually moved performance forward such as rebuilding electronics after a flood, getting real motion with PID and buoyancy changes, modernizing a large ROS codebase, and returning to the long running acoustics problem with a fresh start. The sections below are organized by year and focus on the specific problems I owned, the decisions we made, and the results we earned (making finals with a top 7 finish at competition).

2023-2024 Season Video Highlights

Table of Contents

Third Year

Attacking the Difficult: Back to Acoustics

After the emergency rebuild in my first year (when a capsule flood forced us to drop everything and get the robot operational again) I decided to return to the one project I still considered unfinished: acoustics.

For years this problem had quietly haunted the club. In theory, the robot should be able to localize an underwater pinger by listening with hydrophones and comparing when the signal reaches each sensor. In practice, our robot simply couldn’t find it. Multiple teams had tried, and nothing had produced a reliable solution. So this year we made a deliberate choice: start from scratch.

I began on the hardware side by building a fresh test setup and wiring a circuit to amplify the hydrophone signal. The goal was simple: confirm we could reliably see the pinger signal before getting fancy with filtering and algorithms. That first milestone mattered, and it worked. With a clean amplification stage, we finally had a signal we could test and iterate on with confidence.

From there, we split the problem the right way. While I and others worked through hardware filtering to reduce noise before the signal ever hit our processing pipeline, other team members focused on software filtering to clean up what remained. Once both sides were moving forward, we scaled up to the real test: running all four hydrophones at once.

That’s when we uncovered the kind of issue that makes robotics both painful and honest: the problem wasn’t only signal processing.

During multi-hydrophone testing, we kept seeing inconsistent “time of arrival” differences. After digging deeper, we realized the hydrophones had wires of different lengths. The cables had been cut years ago, and because the information was never documented or passed down, prior teams didn’t even know it was a factor. But wire length matters: different cable lengths introduce different delays, and those delays directly contaminate the timing differences we were using to determine which hydrophone heard the ping first. In other words, the robot wasn’t just bad at acoustics, it was being fed corrupted timing.

At that point, I took a different approach: instead of assuming perfect timing and fighting physics with ideal math, I tried to learn the mapping from messy signals to direction. I built a neural network to predict which signal arrived first. Since four hydrophones create redundant information, I designed the model to use three inputs: each input represented the difference in arrival time relative to a single reference hydrophone. With that setup, the network could estimate the cardinal direction of the pinger with roughly 70% accuracy. Although not perfect, it was reliable after hearing multiple pings.

Meanwhile, one of my teammates translated our breadboard design into a proper PCB. The PCB integrates connections for all four hydrophones, turning our fragile test setup into something repeatable, testable, and ready to iterate on as a system.

This project reminded me why I like the hardest problems: progress comes from refusing to accept the first explanation. Sometimes the obstacle is an algorithm. Sometimes it’s a circuit. And sometimes it’s a piece of missing history that silently breaks everything downstream.

Second Year

ROS 2 Migration: Modernizing the Stack

For my second year I transitioned from the Electrical Team to the Computer Science Team. As ROS 1 is set to be depricated in 2025, I worked to update our Python and C++ code from ROS 1 to ROS 2. This involved a ton of updates and testing to the 50,000+ lines of code in our repository. I spent most of my time in the task planning and utilities sections of our code base, but did do some branching out to other areas as called for (sonar, CV, etc.). And once this was done, I spent a couple weeks linting. Upon completion of the code transition I’ve moved to testing the ROS 2 code using a Jetson Orin Nano on a mock electrical circuit assembled by the Electrical team. This wasn’t the glory work, but gave me a much deeper understanding the robot.

PID Control: Movement Beyond Theory

I once again spent my summer at the pool, this time with our club’s newest underwater robot, Crush. I was trying to make the robot do the one thing it absolutely had to do: move through the water reliably.

Because of setbacks throughout the school year, we entered the summer without having properly tested Crush in the pool. The gap between “built” and “ready” became obvious immediately. At the start of the summer, Crush couldn’t move as directed. It wasn’t even able to travel one meter forward in a predictable way. It drifted, rocked, and behaved more like a floating science project than a navigation capable robot.

A small team of four ran the summer testing, and I was the only member with any background in PID control. Early on, I taught the team how we would approach position control across the robot’s x, y, and z axes, and how to think about tuning: what a stable response should look like, how to interpret overshoot and oscillation, and how to make changes systematically instead of guessing.

My background outside of robotics ended up mattering too. I grew up boating, and that intuition carried over quickly. One of our major improvements wasn’t a PID tweak at all, but a baseline setup problem: the robot’s stable-state thruster power was set too high. We dialed it in so the robot would settle about one meter underwater, but we quickly found that “near zero” power also created problems with drift. By slightly increasing stable thruster power, we gained noticeably better consistency and control.

Even after tuning PID values, we still weren’t getting the behavior we wanted. That’s when I stepped back and looked at the system more physically than mathematically. The robot’s weight distribution was concentrated near the center, which caused rocking and unstable movement. Instead of continuing to force stability through control gains, I redistributed our buoyancy blocks outward, shifting the robot’s buoyancy profile so it naturally resisted roll and pitch. The difference was immediate: Crush became dramatically more stable and began moving cleanly through the pool. One of our key validation runs was a zig-zag traversal from end to end of a lap lane, a practical test of navigation and repeatability which Crush executed with ease.

Then the summer threw us one of the worst surprises you can get in robotics: a small fire. We halted immediately. As the only team member with electrical experience, I took point on the repair: replacing the fuse, swapping burned wiring, and methodically testing the system before we returned to full operation. That recovery mattered not just because we kept going, but because we kept going safely and confidently.

To round out our testing, we had Crush perform 2 barrel rolls, a task that earns extra points at competition. Crush did an amazing job, even outperforming the club’s previous robot.

By the time competition arrived, Crush wasn’t just working, it was dependable. Our new robot successfully navigated the entire pool course, and the Duke team finished in the finals (top 7 out of 40+ teams) for the first time in the club’s history.

For me, that summer was a reminder of what real robotics looks like: control theory, physical design, wiring, troubleshooting, and iteration all happening in the messy real world. Crush didn’t improve because we found one magic setting. It improved because we treated the robot as a full system, and we refused to stop at good enough.

First Year

Can you Hear Me Now?: Navigating the Acoustics Challenges

Joining the Electrical team at Duke Robotics opened the door to an intriguing challenge: improving our robot’s acoustic navigation system. The core problem was that during competition, our robot had to autonomously locate a pinger submerged in a pool. This task proved to be more difficult than anticipated because the water environment distorted the acoustic signals, making it hard for the robot to clearly detect the pinger.

When I came on board, the acoustics project was already behind schedule, with two previous teams having tried and moved on to other areas. Our system at that time utilized three hydrophones positioned on the sides of the robot. The strategy was to determine the pinger’s direction by analyzing which hydrophone received the ping first, second, and third. We then hoped to use this data to identify the correct directional octant. The data was complex since pings come in waves. We isolated the true from false signals by honing in on when the sound wave eclipsed 5 standard deviations from the mean (the upper and lower most horizontal red lines).

My initial approach involved developing a neural network with another team member to analyze this data. Unfortunately, our model’s accuracy was only 60%, which wasn’t sufficient for reliable performance. A deeper dive into the data revealed two major issues: first, some data was corrupted by recordings taken outside the pool, and second, the side-mounted hydrophones were experiencing difficulties from the sound signal interaction with the robot’s structure.

To address these issues, I proposed a new system featuring four hydrophones arranged in a square formation, with each hydrophone positioned just 2 inches apart. This new setup allowed us to place the hydrophones lower on the robot, reducing interference from the robot’s body and the thrusters. By utilizing this four-hydrophone array, we eliminated the need for complex neural network processing. Instead, we could direct the robot to move towards the hydrophone that detected the ping first, streamlining the navigation process.

This approach not only had the promise of improving the robot’s accuracy in detecting the pinger but also brought us back on track with our project timeline. But just before we were able to test the new design, disaster struck.

A Setback and Rebuild: The Unexpected Challenge

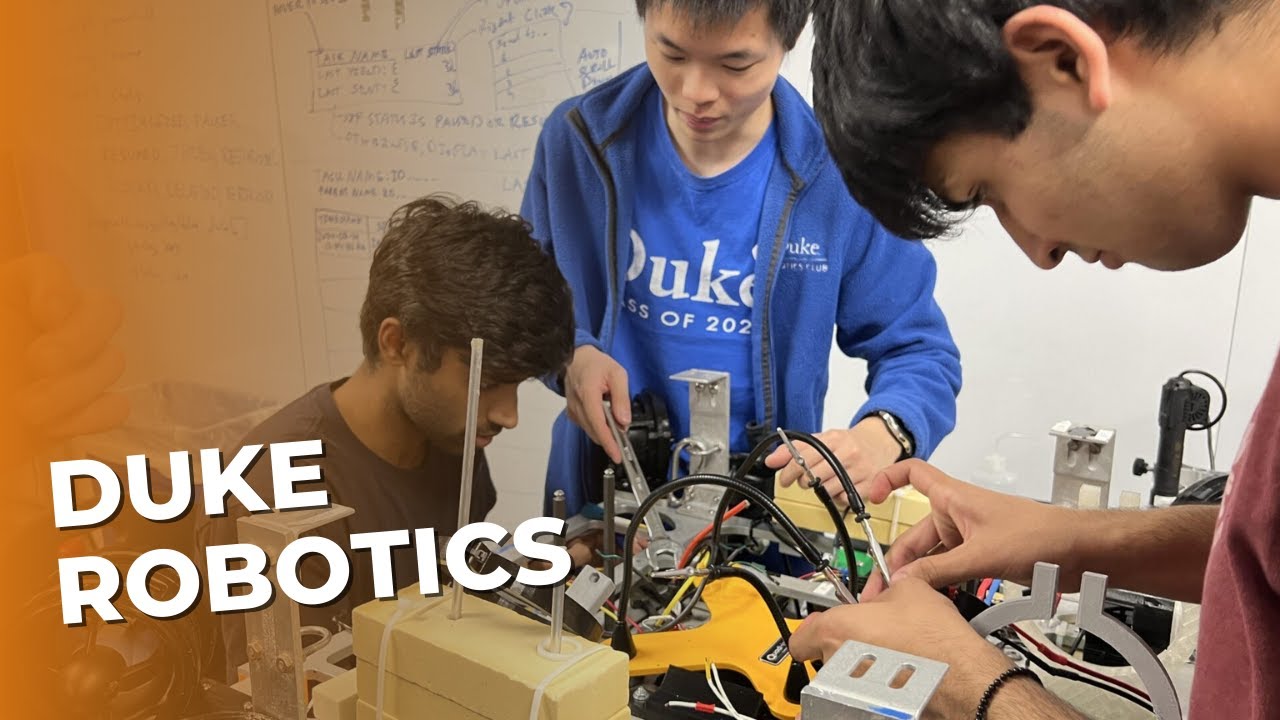

During a routine pool test, the robot was accidentally flooded. This unforeseen mishap forced us to put a halt on the acoustics project and shift our focus to a crucial rebuild of the robot’s electrical system. The flood had damaged several key components, leaving the entire electrical team with the monumental task of repairing and restoring the robot’s functions. Despite the setback, we had a sense of humor about the situation and played the Tintanic movie theme song throughout our next meeting.

I threw myself into the rebuilding process, which involved extensive rewiring and testing. One of my key responsibilities was to address the issues with our Electronic Speed Controllers (ESCs) for the thrusters. As part of the team I rewired, soldered, and performed lots of tests. Once this task was complete I spent hours connecting wires, applying epoxy to seal connections, and organizing the wiring within the robot’s sealed capsule to maximize space and functionality.

The rebuild was a complex and time-consuming task. It took our team nearly two months of hard work and dedication to complete. Despite the setbacks, the extensive effort paid off. Once the robot was reassembled and thoroughly tested, it was not only functional again but performed better than before.

Diving into the Deep End: A Summer of Pool Tests

With the robot back in top shape, I eagerly volunteered to spend my summer immersed in pool tests. Each day, my responsibilities included building and setting up various obstacles in the pool, as well as swimming alongside as the robot navigated them successfully. I also took on the crucial task of keeping the robot away from the pool’s walls and other swim lanes, managing its transportation to and from the pool, and rigorously checking its water-tightness before each test.

Aside from these manual duties, I provided valuable feedback to the Computer Science team about the robot’s performance. This feedback loop was essential for fine-tuning the robot’s behavior and improving its autonomous navigation capabilities. Additionally, I filmed underwater footage for the club’s promotional videos, capturing the robot’s progress and our team’s hard work.

The summer’s efforts bore fruit when, for the first time in years, we successfully completed an autonomous pre-trial competition run midway through the season. This milestone was a testament to the dedication of our team and the significant progress we had made.

Among the many moments of that summer, one particularly memorable event stands out. One day, a fellow team member accidentally dropped a 40 pound weight into the 17 foot deep diving pool. The weight sank quickly to the bottom, and with a bit of determination, I took on the challenge of retrieving it. To everyone’s amazement, I swam down and brought the weight back up on my first try. The lifeguards watching from the poolside were visibly impressed, adding an unexpected highlight to our summer.

Thankful

My experience was more than just a series of technical tests; it was a time of camaraderie, problem solving, and personal achievement. The hard work and dedication not only advanced our robot’s capabilities but also deepened my connection with the team and the project. I am grateful for the opportunities provided to work alongside so many dedicated students. Robotics is learned and performed much better in teams.